Souvenirs, the Homo Faber Edition

Plus, the “temperamental” French musician making killer natural wine, two charming family-owned hotels in “Spain’s Tuscany,” and a breakout Spanish novel newly translated into English

It’s been two weeks since I attended the Homo Faber design fair in Venice, and I’m still thinking about the hundreds of stupefyingly beautiful craft objects on display — jewel-encrusted masks, sculptural blown-glass pieces, wooden chairs resembling the limbs of ancient redwood trees, intricate embroidered panels inspired by a centuries-old Italian dice game. Art festivals can be intimidating, with so much posturing and pretension, but Homo Faber was a joyful (yes, joyful) celebration of craft and creativity, putting many other art world events (at least the ones I’ve attended) to shame.

Setting the tone was the whimsical art direction of Italian film director Luca Guadagnino and Milanese architect Nicolò Rosmarini, who transformed the former Benedictine monastery of Fondazione Giorgio Cini, on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, into something between a old-school confectionary shop and a funhouse, with floor-to-ceiling drapery in spun-sugar pink, 12-meter-high papier-mâché cypress trees, and geometric mirrored surfaces.

I wandered around the exhibition spaces with eyes wide as saucers, standing a bit too close to the objects and resisting the childlike urge to reach out and touch everything. I wasn’t alone. “Have you ever seen something so…?” a man asked his wife as he stared down a porcelain vase by French sculptor Cécile Fouillade, clearly lost for words. Covered in thousands of tubular, needle-like kaolin tissues, it looked so much like a sea sponge that I half-expected its tentacles to twitch to life.

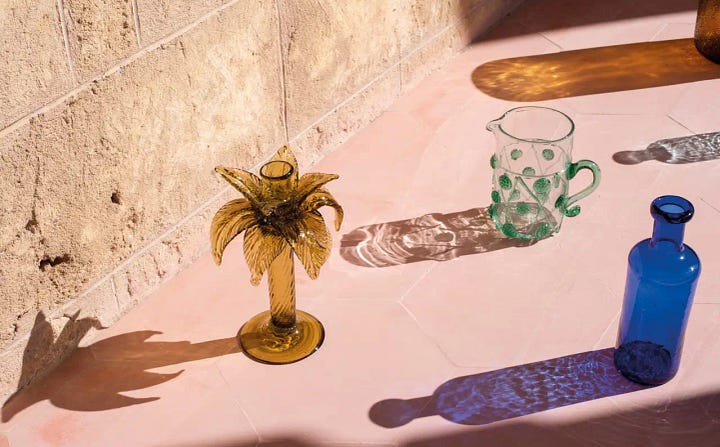

With so much to take in, it helped to approach the fair with a particular focus. I found myself gravitating toward works by Spanish artisans and makers. Some were familiar, such as Gordiola, a family-owned glass brand from Mallorca that was founded in 1719 to cater to the island’s newly-arrived, foreign-born elite. The original designs of the goblets and vases were inspired by Murano glass, but the wares are sturdier than their Italian counterparts and better suited to life on the windy, mountainous island.

Another familiar name was Lladró, the renowned porcelain manufacturer from Valencia (my grandma used to stock up whenever she traveled to Europe!). The brand recently made headlines for its collaboration with Loewe on limited-edition porcelain perfume toppers shaped like carnations, Spain’s national flower. At Homo Faber, visitors were treated to live demonstrations by a Lladró artisan, showcasing the intricate process of crafting these flowers from the brand’s signature milky porcelain—a secret recipe still closely guarded by the Lladró family to this day.

The real treat was discovering new makers like Barcelona-based designer Martin Badia, whose colorful felt, pearl-encrusted masks borrow inspiration from shamanic symbology, Baroque and Art Deco influences, and drag culture. His pieces reflect the “masks” we wear to blend into society and the urge to reveal hidden sides of ourselves, he explained in a recent interview.

In the Inheritance-themed room (each space was themed after a different “journey of life” from birth and love to the afterlife), I discovered the work of Beñat Alberdi, the third generation of Alberdi artisans specializing in the makila—the traditional Basque walking stick. More than just a tool for traversing the region’s forests and rocky terrain, the cane is a cherished heirloom, passed down through generations and gifted during major life events like birthdays or weddings. Today, Alberdi is the only Spanish maker of the Basque walking stick (there are two other workshops in France), and each one is made entirely by hand—a process that can take between five and 10 years (!!) to complete. This is because of the time-intensive technique of making incisions on the wild medlar tree while it is still growing in the Pyrenees. As sap flows through the cuts, the characteristic patterns of the makila are formed. The branches are then cut, debarked, dyed, straightened with heat, and left to dry for up to a decade. Once ready, they are fitted with a brass, nickel, or silver topper, hand-chiseled with Basque motifs. “When someone from the Basque country offers a makila, it’s really important to them — it’s as if they're offering [you] the whole region,” said one French producer of the significance of the object.

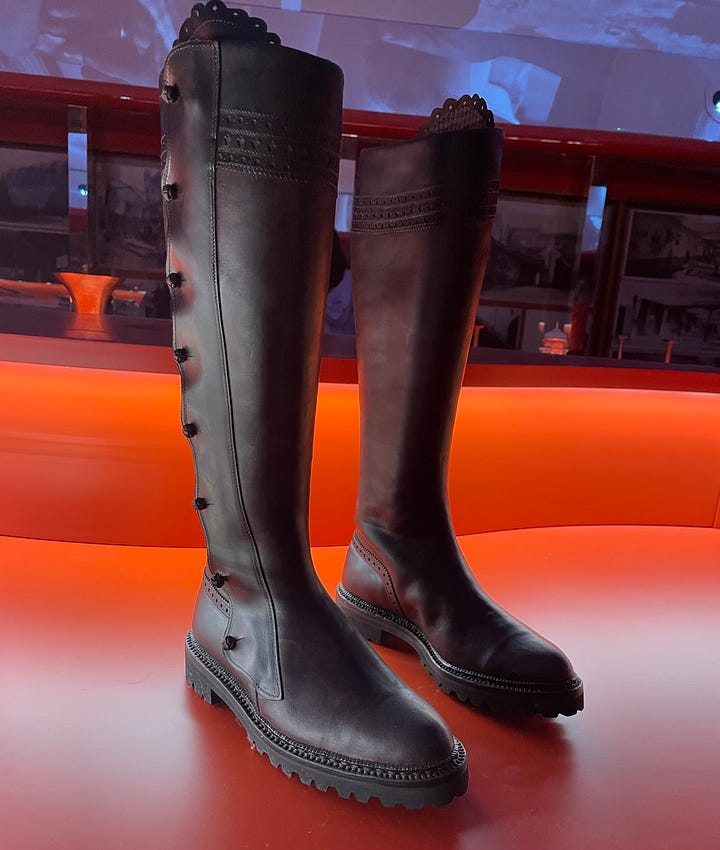

Also in the Inheritance room, I stopped in my tracks to admire a pair of beautiful high-length leather hunting boots, handcrafted by Toledo’s Artesania Muñoz. Founded in 1898 by a cowboy from San Pablo de los Montes, who decided to start working with leather after being injured by a wild bull, the brand specializes in footwear and saddlery crafted from calfskin, cowhide, and suede. Sadly, the third-generation owner fears for the future of his craft, lamenting that today, "It’s easy to say that what you are doing is craftsmanship, even if everything is being done mechanically."

That may be true, but there are reasons to remain hopeful. In place of a traditional gift shop, Homo Faber featured a pop-up for Via Arno, a soon-to-launch craft platform founded by jewelery executive Annia Spiliopoulos and backed by luxury group Richemont, which owns Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Chloé, etc. When it goes live later this year, the platform will showcase objects from more than 300 artisans worldwide, offering “functional crafts” ranging from candlesticks and bicycles to bedding and handmade furniture. Spiliopoulos and her team source these pieces from craft fairs and through the Richemont network. To ensure the highest quality, all participating artisans must be independent, have at least 10 years of experience, and produce goods that are as functional as they are artistic.

While neither luxury brands nor design fairs can single-handedly save these workshops from disappearing or stop the mechanization of age-old traditions, they do give these artisans much-needed visibility and relevance. “Just because craft deals in places with traditions does not make it nostalgic,” remarked Luca Guadagnino in an interview with Wallpaper. “Many objects in the exhibition demonstrate how alive craft is to new ideas, expressions and tools.” Maybe, just maybe, that’s what will keep these joyful and deeply human traditions alive.

Three current obsessions:

Madrid-based novelist Munir Hacehmi’s debut novel made waves when it was published in 2018. The thriller follows four young Spaniards who head to the south of France for a grape harvest but end up working on an industrial chicken farm. Described as “a genre-bending dystopian eco-thriller” with a “punk-like blend of Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives,” Cosas Vivas (Living Things) has just been translated into English by Julia Sanches. If sharp, socially charged storytelling is your thing, this one’s for you.

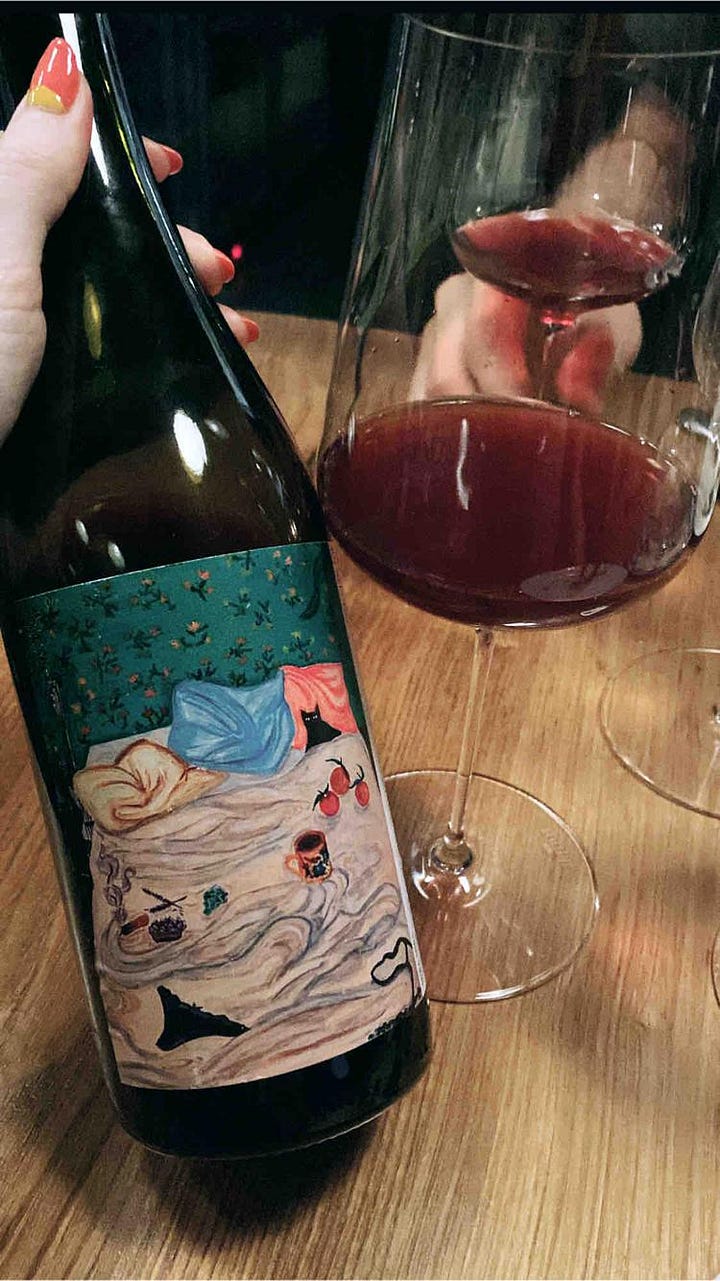

The other week, I had dinner at Barcelona’s Gresca, where the sommelier couldn’t stop raving about a bottle of wine from an eccentric Frenchman who raps, collaborates with the Paris Philharmonic, and is apparently BFFs with Dua Lipa. He also happens to make extremely limited quantities of biodynamic wine on his estate in Bonastre, Tarragona, just south of Barcelona. “He’s completely crazy,” our waiter said of Clovis Ochin, a “temperamental, radical, and demanding” dude who, it turns out, is pretty well known in Paris. Intrigued, we ordered a single-varietal Bobal, and—WOW—it was knock-your-socks-off good: dark fruit, racy acidity, soft tannins. Now I’m desperate to get my hands on more. No idea where (the sommelier said it’s nearly impossible to find), but if anyone has a lead, LMK por favor!

Speaking of wine, I’m gearing up for a late-fall trip to Matarraña, often dubbed the “Tuscany of Spain” for its rolling green hills, medieval towns, and almond and olive tree orchards. While the region doesn’t have the same deep-rooted wine culture as Tuscany (most vineyards were ripped out in the '90s for more lucrative crops), Matarraña is slowly reclaiming its winemaking heritage.

The plan is to pick up a car here in Barcelona and drive 3 hours south, exploring honey-hued towns like La Fresneda, Valderrobres, and Calaceite — the latter, once a haunt for literary icons like Vargas Llosa and García Márquez and some consider to be among the prettiest towns in Spain. I’m dreaming of staying at the family-run La Torre del Visco (from €245/night), a stunning 15th-century estate situated on 220 private acres, with access to hiking trails and horseback riding. There’s also the more affordable and equally as beautiful Mas de La Serra (from €183/night), another family-owned boutique property on the edge of Els Ports Natural Park.

The region’s food scene doesn’t disappoint either. At the century-old Alcala Fonda, you can sample marinated partridges—one of Picasso’s favorites—alongside other Aragonese specialties like Ternasco de Aragon suckling lamb. Also on the menu: local wines from standout producers like Vinos Pedravolta and Venta d’Aubert. The latter is owned by influential Madrid art collectors Christian Bourdais and Eva Albarrán, who also own the region’s cutting-edge Solo Houses art park.